The Symphony of the Senses

Multisensory Processing as the Brain’s First Language

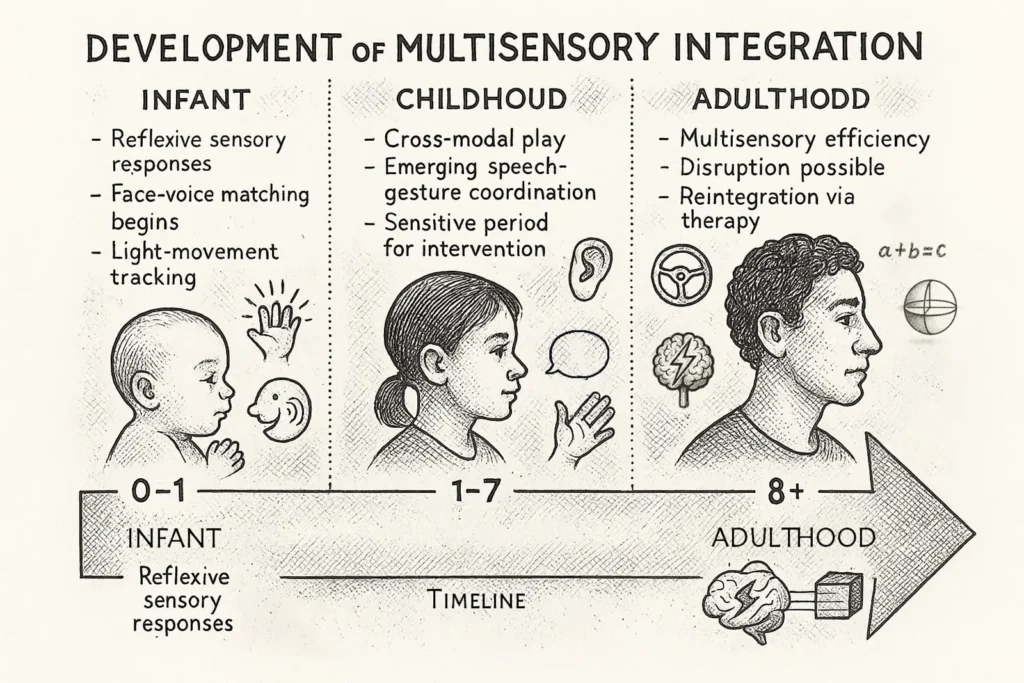

Children experience their world as a constant mix of sensory signals before they develop abilities like speaking and reasoning. The brain receives multiple sensory signals like brightness changes, voice softness, and movement weight as combined overlapping streams rather than separate inputs. The process by which the brain combines multiple sensory inputs into a unified perception is known as multisensory processing. This integrative function is not optional. Every learning process relies upon this foundational substrate. Children experience a fragmented perceptual environment when they encounter vision without context, alongside sound without spatial awareness, and movement without balance. The child starts to structure experience through bodily coordination, followed by cognitive organization when sensory inputs merge and synchronize.

The Roots of Developmental Disruption

Delayed or dysfunctional multisensory integration produces visible effects. Some children will show resistance to bright lights or loud sounds and have trouble keeping eye contact while displaying aimles,s continuous movement. These are not arbitrary behaviors. This behavior represents neurological changes that help the brain manage an excessive or unorganized sensory environment. Many cases of autism and ADHD feature this specific type of multisensory processing dysregulation. The foundational characteristics of these disorders emerge because the brain fails to properly filter incoming sensory information and integrate it into a coherent whole.

Reframing the Child’s Struggle

Behavioral problems often stem from underlying issues with multisensory processing disruptions. Inattention combined with restlessness and emotional volatility often seem like issues related to willpower or discipline. Actually, these problems arise from the brain working hard to manage incomplete sensory input. Understanding this changes the approach. The intervention approach changes from behavioral management to restoring sensory equilibrium. Significant transformation starts at perception’s root, where the senses of sight, hearing, and movement converge.

The Architecture of Integration

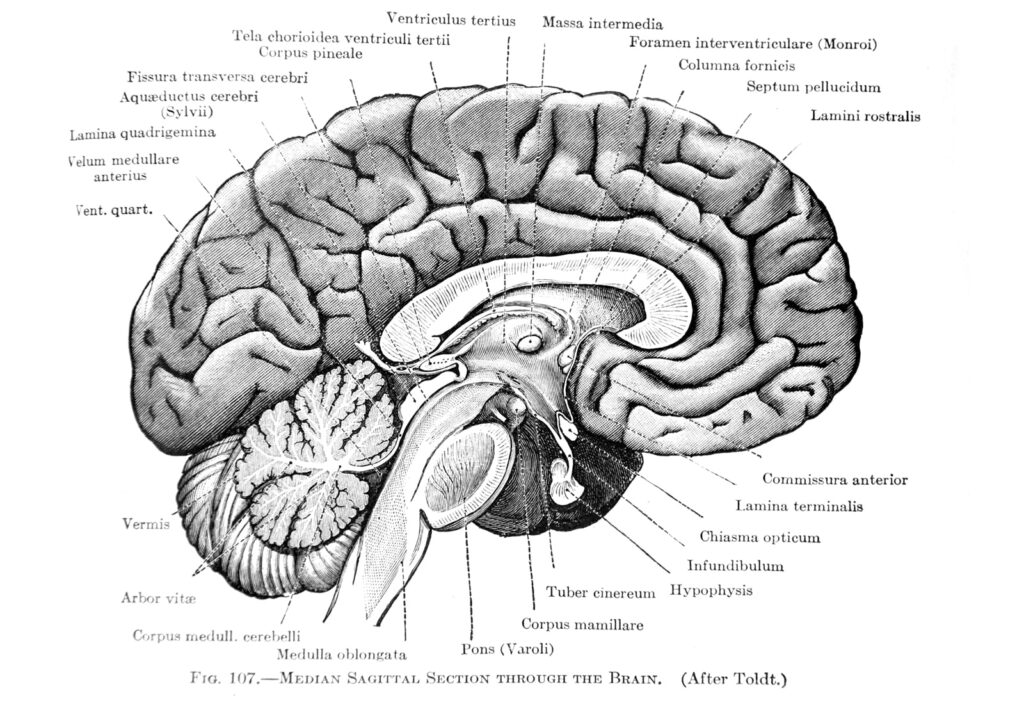

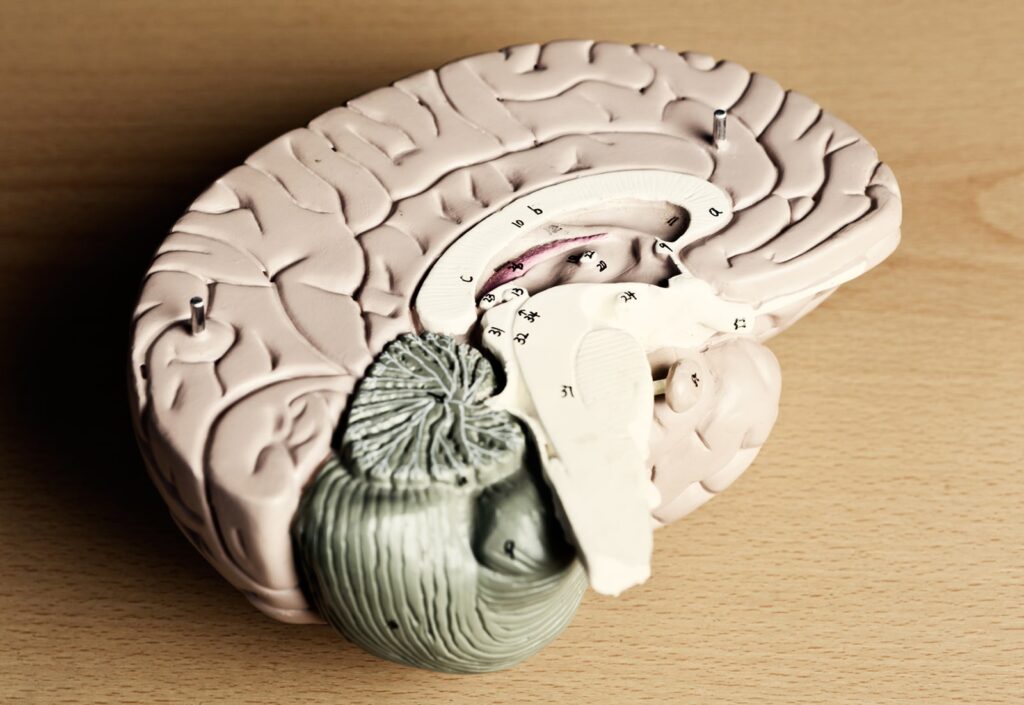

How the Brain Learns to Coordinate Sensory Input

The neurological process by which the brain learns to synchronize sensory information starts in the primitive brain regions. The brain processes multisensory integration in older subcortical regions instead of the cerebral cortex which handles conscious decision-making. The brainstem superior colliculus and thalamus act as initial integration centers that unite visual auditory vestibular and tactile information. These structures start processing sensory inputs from birth or even earlier, enabling newborns to instinctively turn their heads toward voices and match their gaze to moving objects.

Developing children experience refinement of this initial sensory processing work through the activity of cortical regions. As children grow, the parietal and temporal lobes develop sophisticated sensory processing abilities that allow for body spatial mapping, speech-noise discrimination, and understanding facial expressions and environmental signals. Eventually, brain integration processes will operate without conscious effort to free up cognitive capacity for complex activities such as reading comprehension, memory recall, and creative thinking.

But automaticity is hard-earned. The brain remains in a low-efficiency state of high alert when it cannot synchronize properly. The nervous system of children who seem distracted or hyperactive remains engaged in understanding their environment.

When Integration Goes Awry

Sensory integration dysfunction presents with obvious and noticeable effects. The signs are varied—frequent meltdowns, motor clumsiness, poor coordination, speech delays, avoidance of eye contact—but they often share a common theme: the brain is not synthesizing input efficiently. The child fails to build a unified internal representation of the world and instead faces sensory disruptions and overwhelming input.

Children with autism spectrum disorder tend to display extreme responses to sensory input by either overreacting or underreacting. A common sound may trigger distress. Small changes in the surroundings often go completely unnoticed. The child appears absent because their sensory framework for presence remains unfinished, rather than exhibiting detachment.

Children with ADHD face distinct challenges that remain interconnected with other developmental conditions. Sensory input that can’t be organized by importance results in every stimulus being processed with the same intensity. Neither a tag scratching skin nor the flicker of fluorescent lights nor ambient conversation can be ignored. The nervous system experiences constant interruption,s which fragment attention rather than any intentional defiance.

A Shared Thread Across Diagnoses

While the presentation and causes of autism and ADHD vary, they often overlap in one aspect: multisensory misintegration. The key factor in understanding a child’s behavior lies in how their brain interprets sensory input from their environment. Behavioral interventions fail on their own because underlying issues stem from sensory perception rather than intentional deficits.

Research into multisensory misintegration demonstrates the expanded applicability of multisensory therapies. Difficulties with sensory integration extend beyond neurodevelopmental disorders to affect learning delays, emotional regulation problems and certain anxiety-related conditions. Successful interaction with the environment in diverse conditions requires multisensory coherence to achieve organized and confident responses.

Foundations for Cognitive and Emotional Growth

Multisensory Processing as the First Learning System

Before language. Before numbers. Before reasoning. A child understands their environment through bodily experiences which create a constant dialogue between sensory input and physical reactions. That conversation depends on multisensory processing as its fundamental substance. Through multisensory processing the brain develops context while predicting situations and ensuring safety. The child operates without needing to consider their spatial position or identify noises and light intensity when their multisensory system functions correctly. They simply act, explore, learn.

When multisensory integration remains immature or impaired, the brain faces difficulties maintaining its natural rhythm. Movement becomes hesitant as attention wavers while language development proceeds intermittently. The child needs to focus on basic sensory decoding before their brain can handle advanced learning. A strong sensory foundation is essential for the development of emotional regulation along with impulse control and executive function. The higher brain must work harder to manage tasks that would normally function automatically.

Children with ADHD experience an exhausting imbalance that remains undetectable. Multisensory processing inefficiencies mean that tasks such as remaining seated or participating in conversations demand conscious effort. The child seems distracted because their brain is experiencing sensory overload. They’re not disengaged—they’re overwhelmed. Without bottom-up stability, top-down strategies fall flat.

Emotional Regulation Begins in the Senses

An integrated sensory system provides essential support for attention while also creating a foundation for emotional security. The nervous system maintains a defensive position when sensory input becomes chaotic or unpredictable. The child might display symptoms of irritability while also showing social withdrawal or exhibiting volatile behavior combined with persistent anxiety. Children do not choose to behave disruptively because their bodies sense a discord between their physical state and environmental conditions.

Children with autism experience exaggerated levels of dysregulation. Children with autism struggle to understand where their physical self stops and the external world starts. Children with autism experience all sounds simultaneously and observe every detail with the same level of urgency. The need for routines becomes clear because any disruption feels threatening to these children. Their emotional inflexibility stems from sensory experiences and serves as a protective function.

The brain uses multisensory processing to determine important stimuli for focus while blocking out irrelevant information. This process develops skills for switching attention focus while adapting to changing situations and recovering from unexpected events. These are not merely cognitive skills. Their existence relies on the smooth coordination between multiple sensory systems working together at once.

Unlocking Readiness for Learning

Educators typically respond to a child who struggles with reading, writing, speaking or social interaction by teaching them these specific skills. The real challenge when multisensory integration is faulty lies not in understanding but in the ability to access information. The brain remains preoccupied with managing chaotic sensory inputs which prevents effective processing of new information.

Restoring sensory harmony reclaims bandwidth. A child transitions from surviving to exploring and from being stressed to actively participating. Initially the transition appears subtle through reduced fidgeting and improved eye contact with smoother transitions between activities. This neurological coherence will eventually be noticeable during classroom activities, therapy appointments, and everyday home life. The child reaches a stage where he not only processes instructions but also develops new knowledge from it.

Enhancing Development Through Multisensory Interventions

Clinical Applications for Developmental Disorders

The expanding appreciation for multisensory processing as a core capability has created innovative opportunities for therapeutic treatment. Multisensory Training (MST), known as OMST in clinical settings, stands out as one of the most promising approaches within this framework. The method avoids beginning with cognitive exercises and behavioral modification techniques. The starting point of MST coincides with the foundational stage of learning which takes place within our sensory systems.

MST uses simultaneous light stimulation together with vestibular motion and auditory modulation as well as somatosensory input to modify the brain’s information processing patterns. The technique enables automatic processing by activating subcortical networks which manage early sensory integration. MST treatment restores the nervous system’s ability to organize sensations without discomfort.

Clinical applications of MST have produced valuable results for children with various developmental disorders. Children with autism who used to avoid eye contact and struggled with transitions started actively participating in group activities and initiating social interactions. According to parents, their ADHD children demonstrated enhanced concentration abilities and improved emotional control alongside diminished hyperactive behavior shortly after starting MST.

These aren’t isolated anecdotes. Case series and retrospective reviews show consistent gains across domains: Clinical studies demonstrated persistent improvements in four key areas including attention span together with sensory tolerance, language processing abilities and sleep quality. Teachers have noted increased classroom participation. During speech and occupational therapy sessions therapists observed enhanced levels of patient responsiveness. Children who previously felt overwhelmed by daily life challenges now approach their routines with increased coherence and calm.

Preparing the Brain for Higher-Level Therapies

The distinctiveness of MST lies in its sequencing as well as its outcomes. It reinforces the base instead of adding complicated tasks to an unsteady foundation. MST establishes foundational conditions for successful therapy by initially focusing on subcortical sensory hubs.

Traditional interventions often reach a standstill for some children who require the unique approach MST provides. A lack of progress in therapy for speech or behavior might stem from modulation problems instead of motivation issues. MST serves as a preparatory step that enables other therapeutic approaches to work more effectively. When sensory input processing becomes harmonious within the brain it enhances receptivity to learning alongside resilience to difficulties and the ability to maintain consistent attention.

This is especially true in children with complex profiles: Children who experience learning delays alongside emotional dysregulation or who have multiple diagnoses such as autism and ADHD. MST functions as a holistic intervention which reconstructs internal organization to support all subsequent systems in these cases. This method does not provide the child with specific instructions to follow. Through MST children reach a point where they become prepared for learning processes.

A Shift Toward Regulation, Not Control

A subtle yet essential difference exists between behavior control and regulation support. Behavioral therapies typically focus on symptom reduction by modifying how individuals act. MST operates by changing perception. The brain stops from defensive reactions when it experiences smoother sensory input. The child has moved beyond managing their environment to actively participating in it.

MST provides a softer yet deeply established path towards advancement. It doesn’t demand more from the child. Children can experience more from the world without experiencing panic or confusion and without noise interfering.

Integration as Awakening

Moving from Survival to Engagement

A child who experiences fragmented sensory processing encounters a world that lacks consistency and often presents chaotic experiences. Even simple tasks demand vigilance: Children must pay attention to foot placement while ignoring unnecessary sounds to determine where voices originate. The ongoing necessity to interpret sensory input reduces the opportunities for exploration. The child remains engaged because survival demands their attention.

Multisensory integration changes this dynamic. The landscape of experience becomes softer when the brain can effectively receive and organize sensory information with trust. Once sensory integration improves navigation through hallways becomes easier while conversations gain significance and surprises cease to disrupt the present moment. What was once effortful becomes automatic.

This transition is quiet. It often begins not with celebration but with subtle shifts: The first indications of emergence start with simple changes including a more peaceful morning routine and increased openness to unfamiliar experiences along with extended eye contact between people. The first indications of emergence show both sensory disarray resolution and isolation reduction.

From Fragmented Input to Fluid Participation

A well-integrated sensory system provides an essential internal stabilizing point. It tells the child: Your current location becomes apparent to you along with happening events through this guidance about how you should react. Once this anchor is established, higher functions, including empathy and language, develop alongside planning abilities. These functions become unstable when the anchor is missing, similar to how scaffolding lacks stability without its frame.

Children gain freedom to engage in social, emotional, and cognitive activities when MST interventions reestablish their internal anchor. They begin to trust the world again. Self-trust emerges as a critical part of their development.

This isn’t just a therapeutic outcome. It is a neurological milestone. The brain reaches a state where it stops trying to decode current experiences and begins to fully engage with them. Fully. Actively. Calmly.

A Closing Reflection

The concept of multisensory processing extends beyond simply identifying a brain function. Speaking of this topic addresses the learning process through which we find our place in the world. The process of belonging for children starts from the soft, rhythmic interactions they experience through their senses rather than through facts or rules.

When that rhythm is disordered, they stumble. But when it is restored—even gradually—they rise. It emerges slowly and quietly yet powerfully showing us that something fundamental has been restored.

That is the gift of integration. The start of everything emerges through this process for numerous children.